meta balance reviews

Black Cohosh functions as a phytoestrogen, a plant-based compound that acts like estrogen. It is effective in relieving menopausal symptoms when taken in high doses.

We, Health Web Magazine, the owner of this e-commerce website, fully intends to comply with the rules of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) regarding the use of endorsements, testimonials, and general advertising and marketing content. As a visitor to Health Web Magazine you should be aware that we may receive a fee for any products or services sold through this site.

Content

This content may contain all or some of the following – product information, overviews, product specifications, and buying guides. All content is presented as a nominative product overview and registered trademarks, trademarks, and service-marks that appear on Health Web Magazine belong solely to their respective owners. If you see any content that you deem to be factually inaccurate, we ask that you contact us so we can remedy the situation. By doing so, we can continue to provide information that our readers can rely on for truth and accuracy.

Our Top Selections Box – Promotional Sales

Products shown in the section titled ‘Our Top Products’ are those that we promote as the owner and/ or reseller and does not represent all products currently on the market or companies manufacturing such products. In order to comply fully with FTC guidelines, we would like to make it clear that any and all links featured in this section are sales links; whenever a purchase is made via one of these links we will receive compensation. Health Web Magazine is an independently owned website and all opinions expressed on the site are our own or those of our contributors. Regardless of product sponsor relations, all editorial content found on our site is written and presented without bias or prejudice.

Something we believe is that every page on the website should be created for a purpose. Our Quality Page Score is therefore a measurement of how well a page achieves that purpose. A page’s quality score is not an absolute score however, but rather a score relative to other pages on the website that have a similar purpose. It has nothing to do with any product ratings or rankings. It’s our internal auditing tool to measure the quality of the on the page content. There are a number of factors that determine the Page Score of a given page. Landing page quality is a factor in determining Page Score. Landing page quality generally refers to whether or not the overall page contains relevant and original content to the web page visitor. The content quality value of a web page is determined by comparing a page to known quality patterns and each pattern carries a different weighting in how it affects the overall content quality value of a page. We also factor in user generated feedback on this form plus a page quality algorithm. Since web pages content can change, the content quality value of a web page is updated periodically.

Suggested Use

Take 2 capsules daily or as recommended by a healthcare practitioner.

Thorne Meta-Balance, 60 veggie capsules

- A natural approach to menopause

- Helps manage the normal ebbing of hormones*

- Enhances mood*

- Excellent adjunct to Meta-Fem, our multi for women over 40

Each woman’s experience with menopause is different. While many women have only a few problems, others find this phase of life extremely difficult and troubling. Menopausal symptoms are often experienced years before the menstrual cycle ends, during what is known as the perimenopausal period. This may last for as long as 10 years, starting most commonly when a woman is in her early-to-mid 40s.

Because of both the short-term side effects and the long-term health issues associated with conventional hormone replacement therapy, many women desire a more natural approach to allaying some of the unpleasant aspects of menopause. Lifestyle changes can help alleviate some of these uncomfortable conditions. For example, increasing aerobic exercise can reduce hot flashes and improve sleep, while reducing consumption of spicy foods and alcohol may also help reduce hot flashes. In addition, a number of herbs and dietary supplements have been found to be of great benefit during menopause.*

Designed to be taken in addition to the multiple vitamin-mineral Meta-Fem, Meta-Balance is a botanical formula designed to help manage the normal ebbing of hormones associated with menopause, which can result in hot flashes, mood swings, insomnia, night sweats, and poor memory.* Wild yam, black cohosh, Vitex, and dong quai support the natural decrease in female hormone production.* Black cohosh and dong quai have potential estrogenic properties.* Vitex appears to have a stimulating effect on the ovaries.* Progesterone production decreases throughout menopause; wild yam provides natural progesterone-like substances.* Hesperidin methyl chalcone (HMC) is known for its antioxidant properties as well as its ability to strengthen capillaries.* It is also known to stabilize vasomotor activity associated with menopausal hot flashes.*

Ingredients

Chaste tree fruit extract (Vitex agnus-castus), wild yam root (Dioscorea villosa), black cohosh root extract (Actaea racemosa), pycongenol French maritime pine bark extract (Pinus pinaster), hypromellose (cellulose) capsule, microcrystalline cellulose, silicon dioxide

Suggested Use

Take 2 capsules daily or as recommended by a healthcare practitioner.

Store in a cool, dry place. Keep out of reach of children.

*Disclaimer: These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any diseases. As with any dietary supplement, you should consult with a qualified healthcare professional if you are pregnant or nursing, if you have any medical condition, or if you are taking any medication before using this product. Always consult with a healthcare professional before giving supplements to children. Please read full disclaimer here.

Shipping

All orders are shipped directly from our factory warehouse in Chula Vista, California. Orders received before 12PM Pacific Time ship the same day (excluding weekends and holidays). Orders received after 12PM Monday-Friday will ship the following business day. Your tracking number will be emailed from as soon as your order is shipped.

For international shipments, duties and taxes may be applicable. By ordering from this website, you acknowledge that it is your responsibility to pay any duties and taxes.

You can return any unopened or unused product within 30 days on the date on your invoice. Simply send the item back with a copy of your invoice. If you are unhappy with any consumable product, you may return an open item for a refund as long as at least 50% of the original contents remain and the return is done within 30 days of the date on your invoice.

Please report any overages, shortages, or damages within 10 days of receiving your order.

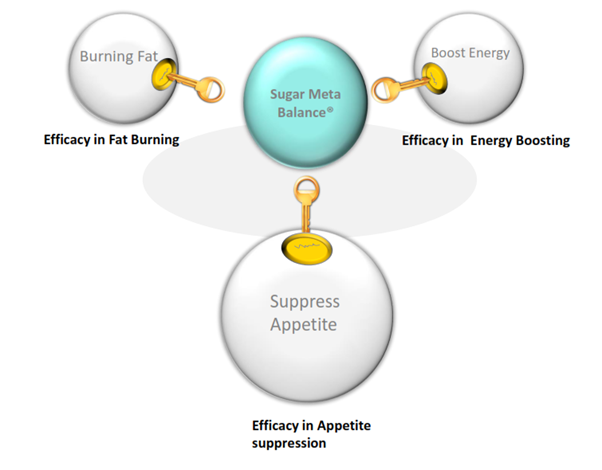

Sugar Meta Balance® is a chromium-based Formulation providing important nutrients needed for the metabolism of sugar, and for energy production and weight management and Designed with nutrients to contribute sugar and carbohydrate metabolism and r. Our formula is superior in 3 different ways :

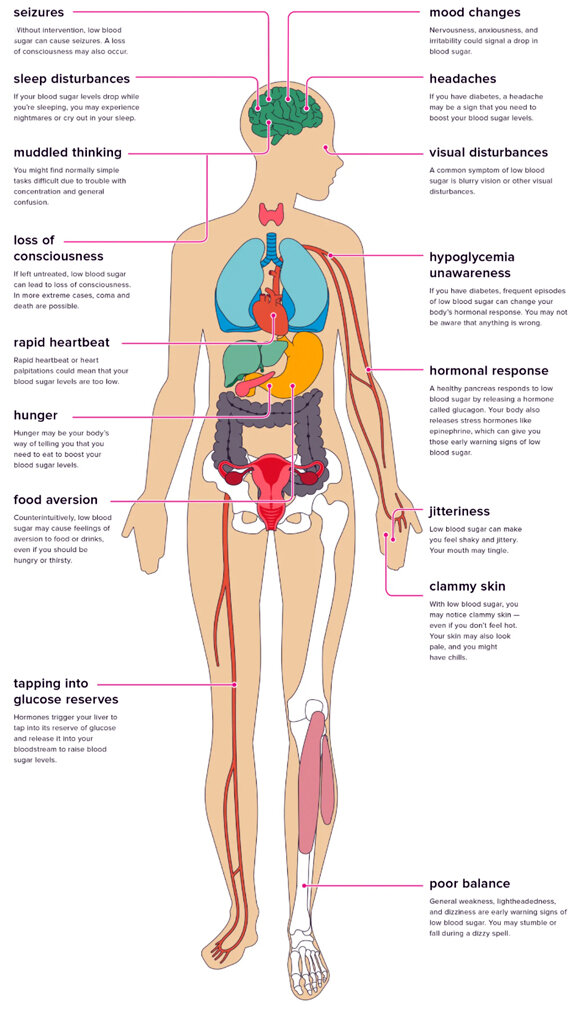

The Effect of the Unstable Blood Sugars

We are going to look at the following symptoms of blood sugar instability. Many of them are symptoms of hypoglycemia, because high blood sugar (hyperglycemia) causes fewer symptoms and is less obvious. You do not need to be sick or overweight to have pre-diabetes or type 2 diabetes.

If your diet is poor, you probably do not metabolize sugar well and show signs of low blood sugar. The Australian Standard Diet (SAD) is rich in processed foods and refined sugars and grains, and low in fiber and nutrition, a storm suitable for turbulent blood sugar levels.

Often, when trying to eat a healthy diet, we substitute refined carbohydrates for high GI, unknowingly. There is a lot of misinformation out there, and cunning food marketing has forced us to know what healthy food is. We all do our best with the information we have, so we formulated Green Nature Sugar Meta Balance®.

How GreenNature Sugar Meta Balance® works !

Sugar Meta Balance® is a chromium-based Formulation providing important nutrients needed for the metabolism of sugar, and for energy production and weight management and Designed with nutrients to contribute sugar and carbohydrate metabolism and r. Our formula is superior in 3 different ways :

Dimensions of weight loss ; for insulin dysfunction which can trigger fat storage and make weight loss impossible and for appetite suppression and high energy . So, we need to convert these clinical facts into a new emotional perception- a perception where Sugar Meta Balance is positioned as the most powerful formula for Blood sugar metabolism and anti-appetite which are main concerns foe weight gain . This is about treating the core of obesity the disease itself.

Why GreenNature Sugar Meta Balance® is different

GreenNature Sugar Meta Balance® contains chromium, an essential nutrient for sugar metabolism, plus zinc and magnesium which also aid sugar metabolism. These nutrients are utilized by the body to aid in efficient uptake of blood sugar into the body cells where it is burned as fuel.

GreenNature Sugar Meta Balance® has been articulated to help:

Supplement nutrients needed for blood sugar metabolism which may be lost due to changes in diet and exercise habits. Support and regulate the production of energy from the metabolism of food Support the metabolism during and after exercise.

A body of evidence derived from clinical trials suggests that exercise, a sub-category of physical activity (PA) that is structured, planned, repetitive, and carried out over a relatively short time frame (from one month to a maximum of 12 months with the most frequent being three months) as outlined by Gillespie et al. (2012) [8] (159 studies; 79,193 participants) and Howe et al. (2011) [13] (94 studies; 9, 821 participants), can maintain balance in higher risk older adults such as those living in institutional care, women, or those with chronic illness (6, 13, 14]. It is also proposed that exercise may even reverse the effects of ageing on balance [17]. Exercise recommendations for older adults at higher risk of falls include individually tailored strength and balance exercise programmes such as Tai Chi programmes [10], and guidelines recommend 120–150 min per week of moderately-intensive PA such as aerobic or muscle strengthening exercise [18,19,20].

Results

A total of 2364 articles were identified by the search strategy. From the title, abstract, and keywords, two reviewers independently identified 82 relevant studies for full text review. From the full text review, 52 were excluded resulting in 30 papers being reviewed (n = 1547 participants). The process, including reasons for exclusions, is shown in Fig. 1 [28].

Observational studies

Design, sample size, and location

Twenty-six studies were observational (one prospective cohort [47], and 25 cross sectional). Sample size ranged from 23 [48] to 170 [47] with an average of 54 participants, but only one study carried out a sample size calculation [49].

Fourteen studies did not specify study location [50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63]; one study was carried out in Japan [47]; four in China [48, 64,65,66]; two in Taiwan [67, 68]; one in the UK [69]; two in US [49, 70]; one in Brazil [71]; and one in France [72].

Participants

Participants across all studies were defined as healthy and resided in the community (62% women; mean age = 66.93 years). Age groups included were: 50–60 years in two studies [52, 66]; 61–70 years in 15 studies [48,49,50,51, 53, 59,60,61,62,63,64, 67,68,69, 71] and 71 years or over in eight studies [47, 54,55,56, 58, 65, 70, 72].

There was a lack of demographics in included studies where only one study reported marital status [57], and one study reported ethnicity and education [49].

Physical activity

All PA interventions were land based except for two studies that included mixed PA with a component of swimming [51, 72]. Sixteen studies included 3D PA (e.g. dance and tai chi) [42] (n = 842 participants), and ten included ‘General’ PA (e.g. walking, cycling) [42] (n = 505 participants). Only one study used an objective measure of PA, an accelerometer, measuring steps per day [47], whilst nine used a variety of validated questionnaire based measures (e.g. Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity (RAPA), Physical Activity Status Score (PASS), Minnesota Leisure Time Physical Activity Questionnaire (MLTPAQ) [48, 49, 59,60,61,62, 64, 66, 69], and 16 did not specify the tool used [50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58, 63, 65, 67, 68, 70,71,72].

All studies included a less active group and a more active group and long-term practice of PA ranging from one to 21 years and over, with two identifying one to five years [47, 52]; eight identifying six to ten years [53, 59, 61, 63, 65, 66, 69, 70]; one identifying 11–15 years [62]; one identifying 16–20 years [67]; and one identifying 21 years and over [51]. Thirteen studies did not specify PA duration [48,49,50, 54,55,56,57,58, 60, 64, 68, 71, 72].

Balance

Overall, studies included multiple balance measures, except for three that included only one measure [51, 59, 71]. Sixteen studies included indirect measures relating to the neuromuscular system (n = 961 participants) [47,48,49,50, 52,53,54, 57, 60, 62,63,64, 66, 69,70,71]. Thirteen studies included indirect measures of cognitive function (n = 805 participants) [48,49,50, 52, 53, 57, 59, 60, 64,65,66, 68, 70]. Only three studies included any sensory system measures (n = 131 participants) [52, 55, 59] and these included proprioception measures. Only one study [50] reported fall rate. Some studies met our inclusion criteria but were excluded from the analyses due to inadequate data and the authors provided no further information on request (n = 159 participants) [56, 58, 67]. Results were estimated from graphical information in seven studies (n = 429 participants) [51, 52, 54, 55, 68, 71, 72].

Secondary outcome measures

Three studies used the Sensory Organisational Test (SOT) [48, 51, 66] (n = 139 participants). Force platforms for the measurement of sway for static or dynamic balance were used in 17 studies (n = 1028 participants) [47,48,49,50, 55, 56, 58,59,60,61,62, 64, 65, 67,68,69, 72]. The ability to maintain balance whilst standing on a tilt board was measured in one study (n = 48 participants) [52].

Quality

Table 2 presents a summary table of the risk of bias of included observational studies and shows that in general studies were of moderate quality (n = 14 studies). All studies rated poor in terms of comparability of participants; the majority (n = 14 studies) failed to provide details relating to selection process, but the measures of balance included in studies were validated and stated in the main objective.

Effects of more PA versus less PA

Primary outcomes

(indirect measures of balance). Initial analyses included 16 variables (20 studies; n = 1053 participants) (Table 3). Sensitivity analysis removed five variables (which are excluded from Table 3) due to their high risk of bias (maximal walking speed, functional reach in back, left and right directions, and range of motion), resulting in only 11 variables (13 studies; 733 participants).

Sensitivity analyses showed significant differences between more and less active groups for two variables (preferred walking speed and SLS), which were not identified in initial analyses, but otherwise did not alter findings (Table 3).

Neuromuscular measures

Table 3 shows that more active groups achieved faster gait speed (SMD 0.66 m/s); better results for two measures of strength using ultra sound tests (SMD 0.57) and isometric knee extension tests (SMD 0.64); better results for three measures of functionality with longer time on SLS test (SMD 1.17s), higher scores on ABC (SMD 1.47), and faster time taken to complete the TUG test (SMD − 0.70s); and better results for one measure of flexibility with greater distances achieved for the functional reach test (forward) (SMD 0.80m).

Sensory measures

Less active groups achieved statistically significant better results for one sensory measure of balance with better results on knee joint repositioning tests (SMD − 1.37).

There was no statistically significant difference between more active and less active groups for neuromuscular measures such as handgrip strength or cognitive measures such as MMSE scores or reaction time.

Secondary outcomes

(direct measures of balance). Twelve variables were included in analyses (14 studies; n = 801 participants) (Table 4: analyses highlighted*). However, for sensitivity analyses three studies were removed, due to high risk of bias (n = 162 participants) leaving ten variables (11 studies; n = 639 participants) for analysis: significance levels decreased for static body stability eyes open and eyes closed (speed).

More active groups achieved statistically significant better results in three secondary outcome measures, with better tilt board results on directional control (SMD 1.02), and maximum excursion (SMD 1.09) as well as SOT visual ratios (SMD 0.13).

There was no statistically significant difference between more and less active groups for other measures of static or dynamic balance.

Intervention studies

Design, sample size, and location

Due to the inclusion criteria only four randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were included [49, 73,74,75]. Sample size ranged from 20 [74] to 60 [49] with an average of 38 participants, and only one study [49] justified sample size.

Of the four studies, one was US based [49] and the country for the remainder was not specified.

Participants

Participants across all studies were defined as healthy and resided in the community (62% women; mean age = 68.78 years), but there was a lack of more detailed demographic information. Average age of participants was 61–70 years in three studies [49, 73, 74], and 71 years or over in one study [75].

Physical activity

All studies included a less active group and a more active group, and all PA interventions were land based where two included ‘3D PA’ (n = 109 participants) (Tai Chi) [49, 75], and two included ‘General PA’ (n = 41 participants) (walking) [73, 74]. Only one study used a validated PA assessment tool used (e.g. PASS) [49].

Intervention duration ranged from a minimum of three months [73, 74] to a maximum of six months [49, 75]. All four provided results at baseline and post-trial commencement, at three months [73], at four months [74], at both two and six months [75], and at both three and six months [49].

Balance

All studies included a neuromuscular balance measure, but only one included a measure of the cognitive system (MMSE) [49], and none included any sensory system measures.

Secondary outcome measures.

One study used the SOT [75], and three used force plate platforms [49, 73, 74].

Quality

Figure 2 presents a summary table of the risk of bias of included intervention studies, and shows a high risk of bias for all studies.

A summary table of review authors’ judgements for each risk of bias item for each study

Effects of more PA versus less PA

Due to the limited number of studies and lack of common outcomes, a best evidence synthesis was explored [46].

Key findings relating to direct measures of balance

Two studies reported direct measures [49, 73], but only one study provided these measures post-intervention measuring neuromuscular system health using gait speed only [73],and found that walking improved gait speed in more active groups. However, the study was at high risk of bias [29] and of low methodological quality (level 3) [46] and so provides limited evidence.

Key findings relating to secondary measures of balance

All four studies reported secondary measures of balance (e.g. SOT vestibular, BoS, and static and dynamic balance), and found that intervention groups had better balance scores. However, all studies were at high risk of bias [29] and of low methodological quality [46], and so evidence is again limited.

Key findings overall

There is limited evidence that free-living PA improves measures of balance in older healthy community-dwelling adults.

Subgroup analyses

The heterogeneity in the nature of the outcome data relating to age, type of PA and duration of effect meant that it was not possible to explore the effects of PA in relation to these variables.

People diagnosed PD often have impaired mobility or poor balance. The literature suggests that balance and mobility problems in people with mild PD may become apparent when more-complex coordination is required under challenging conditions [33], [34]. In Tai Chi exercise, the slow multiple direction movements and mind concentration could increase the strength of the lower limbs, attentiveness and the stability during weight shifting [35], [36]. These factors may contribute to the mobility and balance improvement. Although these improvements indicate that Tai Chi would be effective in promoting neuromuscular rehabilitation, the rationales behind the therapeutic effects in patients’ motor control remain less understood and warrant further exploration.

Discussion

This systematic review demonstrates that Tai Chi showed beneficial effects on motor function, balance and functional mobility in patients with PD. But there was no sufficient evidence to support or refute the value of Tai Chi on gait velocity, step length or gait endurance. Compared with other active therapies, Tai Chi only showed better effects in improving balance. What’s more, there was no sufficient evidence in the follow-up effects of Tai Chi for PD.

It is claimed that Tai Chi is effective in improving motor flexibility and balance for parkinsonian populations [6], [18]. Clearly these claims were tested with eight clinical trials in our systematic review. In this review, most RCTs showed that the implementation of Tai Chi produced positive effects on balance and motor function in people with PD [9], [12]–[14], [16]. The included non-RCT also suggested that Tai Chi yielded better results for functional fitness [17].The strict inclusion criteria increased the confidence in our results. Only studies with detailed and validated data in outcome measures were eligible in our review for conducting meta-analyses. Therefore, our systematic review showed the objective evidence of Tai Chi for PD based on aggregated results. What’s more, detailed subgroup analyses were performed because different control comparators address different questions. The no intervention control is intended to address the question: is Tai Chi an effective therapy for PD. The aggregated results suggested that Tai Chi should be a beneficial therapy in improving motor function, balance and functional mobility in patients with PD. And the meta-analyses of Tai Chi compared with other active therapies address the question of whether Tai Chi is more effective than other active therapies for PD. The results only suggested that Tai Chi should be more effective in improving balance.

Our positive results concur with those from the last systematic review [19]. The systematic review performed by Ni and his colleagues concluded that Tai Chi resulted in promising gains in mobility and balance for pateits with PD, and Tai Chi was safe for PD patients. In this review, however, there was only one study in some subgroup meta-analyses. It was not proper to conduct meta-analysis for which should be performed based at least on two independent studies. In one eligible study, two similar control groups should be combined to create a single pair-wise comparison according to Cochrane handbook, but this systematic review did not perform it. No major adverse events associated with Tai Chi were noted in most eligible studies, but definite conclusion that Tai Chi was safe among PD patients was not possible in Ni’s review. What’s more, two new RCTs of Tai Chi in improving motor function in patients with PD were included in our meta-analyses [16], [17]. So our systematic review provided stronger evidence of Tai Chi in improving motor function in patients with PD.

It would be probably that the objective evidence made our review different from the previous ones [5], [20], [21]. Lee and colleagues concluded that the evidence was insufficient to suggest that Tai Chi was an effective intervention for PD based on three RCTs [22]–[24], one non-RCT [25] and 3 uncontrolled clinical trials [26]–[28] published from 1997 to 2007 [5]. And most of them were only conference abstracts without detailed essential information and validated data of outcomes [22]–[26]. And Toh’s systematic review concluded that there were no firm evidence to support the effectiveness of Tai Chi in improving motor performance in patients with PD [21], but this qualitative systematic review only included 4 RCTs [9], [10], [12], [29], two single-arm intervention studies [27], [30] and two case reports [31], [32]. By contrast, more new studies were recruited in our review [9], [10], [12]–[17]. What’s more, all full texts of seven RCTs [9], [10], [12]–[16] and one non-RCT [17] were published from 2008 to 2014. Another difference may be the detailed meta-analyses performed to investigate the effect of Tai Chi for PD in our systematic review. Hence our systematic review produced more confidence evidence of Tai Chi for PD.

People diagnosed PD often have impaired mobility or poor balance. The literature suggests that balance and mobility problems in people with mild PD may become apparent when more-complex coordination is required under challenging conditions [33], [34]. In Tai Chi exercise, the slow multiple direction movements and mind concentration could increase the strength of the lower limbs, attentiveness and the stability during weight shifting [35], [36]. These factors may contribute to the mobility and balance improvement. Although these improvements indicate that Tai Chi would be effective in promoting neuromuscular rehabilitation, the rationales behind the therapeutic effects in patients’ motor control remain less understood and warrant further exploration.

Although this systematic review appeared to have positive results for PD population, it needs cautious interpretation because there is likely to be several limitations: (a) there was potential location bias due to language barrier, limited retrieving resources and publication bias. And the distorting effects of publication and location bias on systematic reviews are well documented [37], [38]; (b) there was one non-RCT in the meta-analysis of the motor function, but it did not affect the aggregated results. What’s more, it also contributed valuable information to the evidence of Tai Chi for PD, especially on motor function; (c) our aggregated results may be affected by styles and dosing parameters of Tai Chi in eligible studies, such as different styles (Yang-style, Wu-style, 24-short form, etc.), duration (time of each Tai Chi), frequency (sessions of Tai Chi per week); (d) there were less eligible studies in some subgroups meta-analyses due to strict eligibility criteria in our review. It may influence aggregated results, but low eligibility criteria would generate more doubtful results; (e) the evaluation on the follow-up effect of Tai Chi for PD was insufficient in eligible studies. So the current results should be interpreted with caution and future studies should pay more attention to the follow-up effect; (f) although no major adverse events associated with Tai Chi were noted in included studies, definite conclusions were not possible. It only can be assumed that Tai Chi is a therapeutic option with low risk of injury.