elemor reviews

As we age the composition, texture and appearance of our skin changes. Signs of skin aging include wrinkles, fine lines, loss of moisture, uneven tone, and dull, tired-looking skin. There are countless anti-wrinkle creams on the market promising to make skin look and feel younger. Many anti-wrinkle creams promise everything short of a facelift or to provide the much sought after “fountain of youth”. In reality most are just moisturizers marketed as anti-aging products.

We, Health Web Magazine, the owner of this e-commerce website, fully intends to comply with the rules of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) regarding the use of endorsements, testimonials, and general advertising and marketing content. As a visitor to Health Web Magazine you should be aware that we may receive a fee for any products or services sold through this site.

Content

This content may contain all or some of the following – product information, overviews, product specifications, and buying guides. All content is presented as a nominative product overview and registered trademarks, trademarks, and service-marks that appear on Health Web Magazine belong solely to their respective owners. If you see any content that you deem to be factually inaccurate, we ask that you contact us so we can remedy the situation. By doing so, we can continue to provide information that our readers can rely on for truth and accuracy.

Our Top Selections Box – Promotional Sales

Products shown in the section titled ‘Our Top Products’ are those that we promote as the owner and/ or reseller and does not represent all products currently on the market or companies manufacturing such products. In order to comply fully with FTC guidelines, we would like to make it clear that any and all links featured in this section are sales links; whenever a purchase is made via one of these links we will receive compensation. Health Web Magazine is an independently owned website and all opinions expressed on the site are our own or those of our contributors. Regardless of product sponsor relations, all editorial content found on our site is written and presented without bias or prejudice.

Something we believe is that every page on the website should be created for a purpose. Our Quality Page Score is therefore a measurement of how well a page achieves that purpose. A page’s quality score is not an absolute score however, but rather a score relative to other pages on the website that have a similar purpose. It has nothing to do with any product ratings or rankings. It’s our internal auditing tool to measure the quality of the on the page content. There are a number of factors that determine the Page Score of a given page. Landing page quality is a factor in determining Page Score. Landing page quality generally refers to whether or not the overall page contains relevant and original content to the web page visitor. The content quality value of a web page is determined by comparing a page to known quality patterns and each pattern carries a different weighting in how it affects the overall content quality value of a page. We also factor in user generated feedback on this form plus a page quality algorithm. Since web pages content can change, the content quality value of a web page is updated periodically.

What does this product or service do well?

Eleanor

Elevate your guest experience. Guaranteed. Made for Resorts.

Ratings Snapshot

Ranked #2 out of 29 in Concierge Software

Eleanor Enterprises’s customer support processes haven’t yet been verified by Hotel Tech Report.

Eleanor Overview

Eleanor Overview

Manage and enhance your relationship with your guests with our unified resort wide guest experience management platform, while unlocking operational efficiencies and boosting incremental revenue. Made for Resorts.

About Eleanor Enterprises View website

With over 15 years of hands-on experience at resorts, Eleanor was born out of a desire to help improve the guest experience, remove inefficiencies and boost inc.

Integrates with

- Property Management Systems

What customers love about Eleanor

-Saved a lot of man hours for our resort team on the simple task of making reservations for our activities -Good guest app that allows pre-arrival bookings and upselling -Easy setup & training thanks to the Eleanor tea.

Resort Manager from Resort

• All guest experiences, regardless of department, together with their availability can be viewed and booked from one central place • Great data on our guests and their real preferences • Very user friendly and if .

IT Manager from Resort

The front-end look, user friendly and customisation are done to meet our expectations. Event booking and managing events are one of best feature in this app and we are very happy about it. Payment and checkout is anothe.

IT Manager from Resort

Very well polished app with easy navigation. Everything can be accessed by few clicks. Guests can book variety of activities and restaurants from the comfort of their room. The restaurants dining menu is very helpful. Gu.

Expert Q&A and Partner Recommendations

What does this product or service do well?

A fantastic guest-friendly and staff-friendly application that can and will enhance the guest experience of any resort or a hotel. It’s simple for guests to plan itinerary ahead of time and they can check-in via the app, contactless style. Increased revenue due to increased visibility and promotion .

by David Ganly (hconnect) on December 07, 2021

Showing all answers to: “What does this product or service do well?”

What differentiates this product or service from the competition?

For hconnect an integrator the onboarding process can be somethings be challenging, with the Eleanor application it is easy and straight forward. The Eleanor team are very responsive and easy to work with and we are happy to partner with them.

by David Ganly (hconnect) on December 07, 2021

Showing all answers to: “What differentiates this product or service from the competition?”

Based on your experience with this product or service, if you could give one piece of advice to a hotelier considering this product or service, what would it be?

Hoteliers should avoid disappointment when selecting products by using trial periods or recommendations. Work with operation teams to ensure the product will do what you expect it to do. I am sure you don’t be disappointed with Eleanor.

Impressively, the author does not sugarcoat or diminish the casual racism and xenophobia of the age, highlighting FDR’s use of the N-word and comfort with segregation, as well as the well-documented anti-Asian racism undergirding the internment of Japanese citizens during the second world war. Indeed, Michaelis’s framing of these deficiencies in American political life helps us to trace their provenance in our own era and allows us to see what Eleanor was up against in her bravest as well as her most timid moments.

Eleanor review: sensitive and superb biography of a true American giant

A s the 2020 US presidential election winds toward a tortuous and dysfunctional certification, it is tempting to imagine that intrigue and machinations belong only to this particular heated moment in American life and history. That would be wrong.

There is always intrigue in American politics, though nothing approaching the current state of near-sedition. We would be also be wrong if we dated the role of iconic first ladies only as far back as Michelle Obama and Hillary Clinton, or even Jackie Kennedy. Before there was Jackie or Hillary or Michelle, there was Eleanor. Niece to one president, wife to another; activist, global citizen; mother of the Democratic party in the mid-20th century, when the mother of the party was still a thing.

You will find all these identities in David Michaelis’s elegant new biography of Eleanor Roosevelt, but the beauty of this robust volume is that there are so many more Eleanors to meet. Awkward girl; yearning and unappreciated wife; shy but committed romantic; resolute partner; distant mother. Michaelis, a veteran biographer, shows us all these many faces, rendering a complex and sensitive portrait of a woman who bridged the 19th and 20th centuries, reimagining herself many times with both courage and resilience.

Born into the strictures of upper-class white womanhood, Eleanor was conversant with and adjacent to political power from an early age. Born to a beautiful, critical mother and an affectionate, drug- and alcohol-addicted father, she might well have been identified in the 21st century as an adult child of an alcoholic, with all the needy and compliant behavior implied. Her mother, Anna, consumed with keeping up appearances, was no better than any other woman of her class; indeed, her constant mockery of the young Eleanor certainly compounded the child’s insecurity and desire to truly belong. Michaelis writes with great sensitivity, utilizing Eleanor’s own recollections and other research materials to set the backdrop for recurring themes in his young subject’s life, including her mother’s “ritualized humiliation … as often as not in front of company”, including her mocking nickname of “Granny”.

With both parents and a brother dead by the time she was 10, Eleanor found herself introduced to tragedy – as well as to something steadfast within herself: “No matter what happened to one in this world, one had to adjust to it.” And adjust she did, to her grandmother’s strictures, her mother-in-law’s disdain, the ambitions of her husband, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. This biography gives equal weight to Eleanor’s personal and political longings, her frustrations with her husband and her fury at his indiscretions; and her own loves, requited and otherwise.

At the same time, however, Michaelis reveals, again and again, that Eleanor found her truest self through duty, hard work and sometimes punishing overachievement. She felt most loved in partnership and was misled by the illusion of it. Longing to be the center of one person’s love, she settled instead for the larger, public love of a generation as she wrote, traveled and agitated to change the world. What is especially refreshing about this biography are the ways in which Michaelis refuses to hide the fact that Eleanor’s struggles for justice had limits, drawn not only by her grudging acceptance of a political spouse’s role, but also through the limitations of her race and class.

Impressively, the author does not sugarcoat or diminish the casual racism and xenophobia of the age, highlighting FDR’s use of the N-word and comfort with segregation, as well as the well-documented anti-Asian racism undergirding the internment of Japanese citizens during the second world war. Indeed, Michaelis’s framing of these deficiencies in American political life helps us to trace their provenance in our own era and allows us to see what Eleanor was up against in her bravest as well as her most timid moments.

Her commitment to global citizenship and human rights served to mirror white activists in that period as well as this one: they find the courage to fight for human rights and dignity in the far corners of the globe yet choke at the exact moment when their courage could be most effective. She found herself in full command of the symbolic gesture – making it possible for Marian Anderson to sing on the steps of the Lincoln memorial and resigning from the Daughters of the American Revolution but refusing to attend the concert herself, at a moment when such a symbolic gesture might have made a greater difference.

These sections will not surprise many African or Japanese Americans. Such readers will likely have personal experience with the failures of white Americans who talk a good game about democracy and equal justice under law, but who can’t deliver when the chips are down. Indeed, Michaelis does such an excellent job of outlining Eleanor’s grueling work to bring to fruition the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that the country’s domestic deficiencies during and after FDR’s presidency are drawn in sharp relief.

Hillary Clinton unveils a new statue of Eleanor Roosevelt in Oxford, on 8 October 2018, the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Photograph: Victoria Jones/PA

The breadth of Michaelis’s research has an unexpected side effect: the introduction and early appearances in Eleanor’s sweeping story of future American political and social figures. Readers will come upon “Bull” Conner, J Edgar Hoover, Thurgood Marshall and others in between, and get a foreshadowing of their roles in the story of America. (Spoiler alert: some people never change.)

Michaelis details innumerable stories of people and events in Eleanor’s life, from her years as the increasingly engaged first lady to her roles in Democratic Party politics to her work as a newspaper columnist and speaker after Franklin’s death in 1945. Time and again, she opened herself to different people and experiences that helped shape her life.

Eleanor

One day as a teenager growing up in Jackson Heights, Queens, I stood in an excited crowd waving at Eleanor Roosevelt (1884–1962) as she rode by in a motorcade down 82nd Street, a main thoroughfare. This was in the 1950s, several years before her death. By then, “American schoolchildren thought of her as a living saint,” writes David Michaelis, author of Eleanor. I still do.

I knew little then about her privileged childhood, her marriage to the man who would become President Franklin D. Roosevelt, or their partnership during the Depression and war years. Nor about the male and female intimates in her life. For me and many others my age, she was a great advocate for the poor, the unfortunate, and the mistreated. Says Michaelis, “She was the world’s foremost champion of human rights.”

In this sympathetic portrait, the author gives us the full story of Eleanor at each evolving stage of her life. Her growth was remarkable. Her early years in a prominent New York family were comfortable, but offered little emotional sustenance. She was a plain child. Her uncaring mother called her “Granny.” Her father, an alcoholic, was in and out of rehabs. Eleanor adored him. She “found bliss dancing for her father and receiving his unfettered adoration in return,” writes the author.

To remove her from the erratic orbit of the man who meant most to her, she was sent away to a convent.

“Eleanor, I hardly know what’s to happen to you,” her mother was supposed to have said. “You’re so plain that you really have nothing to do except to be good.”

Raised by her grandmother after the early deaths of her parents, she was a fearful, anxious teenager, always a people-pleaser. While away at school in France, she gained some confidence, and returned home to plunge into settlement work, determined to do something more than please. Her eyes began to open, and she pointed the way for others: After visiting a New York tenement family with her, Franklin said, “My God, I didn’t know people lived like that.”

Gradually, Eleanor outgrew the conventions and prejudices of her blue blood family, transcending their “condescension and social restrictions,” in the words of one friend, a state trooper, who introduced her to “prole joys—guns, cars, tourist cars, vernacular speech.” With him she could relax and smile, writes Michaelis.

Franklin, her husband, was a different matter. Life partners, but not emotional intimates, each pursued love affairs—he with social secretary Lucy Mercer, she with AP reporter Lorena Hickok.

Michaelis details innumerable stories of people and events in Eleanor’s life, from her years as the increasingly engaged first lady to her roles in Democratic Party politics to her work as a newspaper columnist and speaker after Franklin’s death in 1945. Time and again, she opened herself to different people and experiences that helped shape her life.

Much of Eleanor will be familiar to many readers, but Michaelis’s rendering is especially bright and a pleasure to read. Few other books reveal the fascinating inner journey that transformed Eleanor from an emotionally choked-off young woman into a mature leader who inspired millions.

“You are something so rare,” Jackie Kennedy once told her, “and so good for all women of my age to have to emulate—a great lady.”

Her friend Martha Gellhorn called Eleanor “more than a saint, a saint who took on all the experiences of everyday life, an absolutely unfrightened selfless woman whose heart never went wrong.”

Who would not cheer for such a person in a passing motorcade?

Joseph Barbato is an author and journalist whose books include Writing for a Good Cause (Touchstone) and Heart of the Land: Essays on Last Great Places (Vintage). He has been a columnist and contributing editor at Publishers Weekly, and has written for the book pages of ther Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, and USA Today. He has served as a juror for the annual Kirkus Prize and worked as a communications director for many years at NYU and The Nature Conservancy.

If Hollywood isn’t offering you the roles you want, the advice to screen actors always goes, “Write something for yourself.”

Elemor reviews

If Hollywood isn’t offering you the roles you want, the advice to screen actors always goes, “Write something for yourself.”

So it was with Annika Marks, a familiar face (“The World Without You,” TV’s “Goliath,” “Waco” and “The Last Tycoon”) if not a marquee name. But with “Killing Eleanor,” she’s written not just a plum role for herself — an ex-dancer/junkie trapped in the lies she’s built her life around — but a lovely curtain call part for veteran character actress Jenny O’Hara (“Mystic River,” and TV’s “The Mindy Project” and “Transparent”).

“Eleanor” is an indie dramedy with weight, biting wit and heart, a movie that generously offers meaty roles for Jane Kaczmarek and Camryn Manheim, who help this “road comedy/caper comedy” turn, on a dime, into a film of substance and one that’s kind of heartbreaking.

The end, when it comes, is rarely pretty. Eleanor’s old enough to know that. Living in a nursing home, medicated, her life prolonged in ways that make no sense to her, all she wants is control over her end.

That’s why she (O’Hara) seeks out Natalie (Marks) in Natalie’s mother’s (Kaczmarek) nail salon. Fresh from an AA meeting but still using Adderall, back to living with her parents in her 30s, lying about everything and to everyone she meets, Natalie’s at the narcissistic end of the “rehab” spectrum, wrapped up in her own mess.

And then this stranger with a nursing home ID bracelet stalks in and barks, “It’s time. You OWE me.”

An ancient IOU has come due. Yes, she knew Eleanor years ago. Her plea, spat out with a splattering of profanity, is presented as a demand.

“I want you to help me die.”

And Natalie, distracted by her family’s “intervention,” her harridan sister’s (Betsy Brandt) political campaign demands and her drug cravings, says “OK” for reasons that make no sense until you consider the bad decisions, impulse control and lies meant to cover lies way she gets through her day.

“Killing Eleanor” invites us to consider, through messed-up Natalie, whether we’d grant such a wish, and where’d we begin if we expect to go through with this. Not that we’re sure lying Natalie will.

Marks briskly sketches in Natalie’s “issues” and her family’s range of reactions to them. Mom is mistrusting behind an upbeat and supportive face, Dad (Chris Mulkey), is a doctor too distracted to dig in, and sister Anya (Brandt)? She is WAY past over Natalie’s nonsense.

We’re treated to the blizzard of lies it takes for Natalie just to get in to see Eleanor once the nursing home has taken her “home.” We see the DIY way Eleanor effects her escape and the impromptu road trip they take through the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, ostensibly to “buy drugs” in Canada, where “assisted suicide” is supposedly easier to pull off.

The dialogue is peppered with flippant cracks about death and old age, from Mom’s “if I ever get like that, shoot me” to nervous nail-biter Natalie’s many jokes about what Eleanor wants and ways Eleanor might accomplish it.

Eleanor hisses “Those things’ll kill you” about Natalie’s smoking.

They run out of gas, so let’s flag down a trucker. Get into a semi “with a complete stranger?”

“Maybe he’s a psycho killer and he’ll solve our problem for us.”

Better let the service station attendant fill the gas can rather than risk Natalie “soaking us all with gasoline.” Pause. “Although…”

But a stranger (Manheim) who picks them up understands their quest and puts it in perspective. Natalie’s personal journey to redemption steps to the fore and “Killing Eleanor” finds its heart.

Marks’ performance begins with a series of tics — nervous, smoking, nail-biting, ransacking the family’s vacation condo for drugs (as antic drum solos accentuate her mania) — and evolves into a sort of stages-of-death-and-dying “acceptance.” Nice and subtle.

And O’Hara’s Eleanor travels from grousing, bitter old woman to vamping, over-the-top Christian “sponsor” to cover up another of Natalie’s lies, and beyond — a compact, lived-in turn that never feels false.

Yes, the screenplay gives away twists and points to an obvious finale early. But Marks, O’Hara & Co. never let us forget that whether of not you wind up “Killing Eleanor,” it’s the journey, not the destination, that matters most.

Rating: unrated, drug abuse, profanity

Cast: Annika Marks, Jenny O’Hara, Jane Kaczmarek, Chris Mukley, Betsy Brandt and Camryn Manheim

Credits: Directed by Rich Newey, scripted by Annika Marks. A 1091 release.

Eleanor and Franklin married in 1905 and she quickly had six children, five of whom survived. Her public story began in 1921, when Franklin came down with polio. The disease robbed him of his ability to walk, and Eleanor became his legs. She was an unstoppable force in his successful campaign for governor of New York in 1928. Her energy level always seemed to be someplace between prodigious and terrifying. Following her through the pre-White House era, you can already see how she’d evolve into a first lady who visited with more than 400,000 troops in the South Pacific in World War II.

Eleanor Roosevelt, First Among First Ladies

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

- Oct. 6, 2020

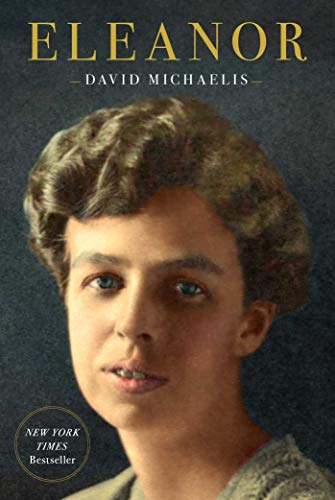

ELEANOR

By David Michaelis

Eleanor Roosevelt was the most important first lady in American history. Or at least until Hillary Clinton. But when Hillary was in the White House she claimed she was communing with Eleanor’s spirit, looking for inspiration.

Eleanor came from an important family — Uncle Theodore, after all, was president. But her upbringing was so grim that it’s a wonder she emerged functional, let alone one of our nation’s great humanitarians. Her haughty mother humiliated her by calling her “Granny.” Her alcoholic father was the beloved parent, but hardly someone you could count on in a pinch. Once she reached adolescence, Eleanor was installing triple locks on her bedroom door “to keep my uncles out.”

She compensated for feelings of unattractiveness and rejection with good works. As she grew to adulthood, Eleanor threw herself into the settlement house movement to serve the poor. Her boyfriend Franklin was impressed — and a little shocked — by her activities. He announced after she took him on a tour of tenement life on the Lower East Side: “My God, I didn’t know people lived like that.”

Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt were distant cousins in a family that would probably not have chosen Franklin as most likely to succeed. The joke was that “F.D.R.” stood for “Feather Duster Roosevelt.” But he had grand ambitions, and David Michaelis, the author of biographies of Charles Schulz and N. C. Wyeth, suggests he “was wise enough to know (as only a boy named ‘Feather Duster’ knows) that if his will to power was to be taken seriously, he needed a woman of urgency by his side.”

Michaelis’s “Eleanor” is the first major single-volume biography in more than half a century, and a terrific resource for people who aren’t ready to tackle Blanche Wiesen Cook’s heroic three-volume work. At more than 700 pages it’s hardly a quick read, but it’s a great resource for people who don’t know a whole lot about her.

Eleanor and Franklin married in 1905 and she quickly had six children, five of whom survived. Her public story began in 1921, when Franklin came down with polio. The disease robbed him of his ability to walk, and Eleanor became his legs. She was an unstoppable force in his successful campaign for governor of New York in 1928. Her energy level always seemed to be someplace between prodigious and terrifying. Following her through the pre-White House era, you can already see how she’d evolve into a first lady who visited with more than 400,000 troops in the South Pacific in World War II.

“I’m only being active until you can be again,” she wrote him. “It isn’t such a great desire on my part to serve the world & I’ll fall into habits of sloth quite easily!”

The marriage, sadly, was not working out nearly as well in private as it was in public. Eleanor, Michaelis says, “found the sexual side of their marriage less than pleasant and perhaps so did he.” If so, Franklin’s diffidence was apparently limited to his wife. Back in 1917 Eleanor discovered he had been having an affair with her social secretary, Lucy Mercer, which Michaelis suggests was an important moment in American history. Maybe it was, since the marriage became more of a political partnership than romantic attachment. Eleanor agreed to stay and Franklin vowed he would never see Lucy again, in what turned out to be one of American history’s more famous broken promises.

Eleanor’s own romantic life gets thorough treatment, given that much or all of it seemed to involve crushes rather than consummation. There was Earl Miller, a state trooper who tutored her in self-defense. And Lorena Hickok, an Associated Press reporter who would eventually leave her job to work in the White House. Eleanor was definitely in her thrall. (“Oh! I want to put my arms around you. I ache to hold you close.”) But women of their generation often wrote letters to friends that sounded like mash notes and historians have had a hard time with the very specific question of whether Eleanor and her “Hick” did the deed. Michaelis’s description of their relationship suggests the physical details didn’t matter.

What’s really important to history is Eleanor’s public life once Franklin was elected president in 1932. She wanted to bring him stories about the real America and she traveled around the country bearing witness to the grief of its Depression-racked citizens. It was not at all what Americans expected of a first lady but as time went on, Michaelis writes, “fewer minded that the wife of the president was driving alone by night through villages and four-corners hamlets and stopping for gas on the outskirts of town.”

Michaelis is careful to point out the ways in which the younger Eleanor was not ahead of her time. He has a collection of examples of her early anti-Semitism. And she told white Southerners she “quite understood” their point of view on racial matters.

But she evolved, way ahead of most of the nation. In 1938, she attended a memorable meeting of human rights groups in Birmingham, where the not-yet-notorious Sheriff Bull Connor banned integrated audiences. So Eleanor sat on the side where the Black participants were cordoned off. When the police ordered her to move, she put her chair in the aisle and sat down.

After Pearl Harbor, Eleanor insisted on going to the Pacific war zone to support the troops. A visitor asked Franklin if that kind of trip wouldn’t leave her exhausted. “No,” her husband replied. “but she will tire everybody else.”

Eleanor’s worry was different — she was afraid that the troops would hear rumors about a female visitor, imagine a glamorous entertainer and be disappointed when she walked into the room. Not a problem. She toured the hospitals, speaking to each wounded soldier, and got up at 5 in the morning so she could have breakfast with the enlisted men. Fleet Adm. Bull Halsey, who had lobbied vigorously against her trip, recanted, declaring, “She alone accomplished more good than any other person or any group of persons who passed through my area.”

Eleanor was not with Franklin when he died of a cerebral hemorrhage at the presidential retreat in Warm Springs, Ga., in 1945. And she was shocked when she discovered his old lover Lucy Mercer had been there, and that her daughter Anna had set up Mercer’s trip to give her ailing father the kind of comfort his wife never seemed able to provide.

Harry Truman cannily appointed Eleanor to a high-profile job in the new United Nations General Assembly, which was about to open in London. Early on she kept a low profile, working “six and a half days a week, 18 to 20 hours a day.” Her goal was adoption of a Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In 1948, it happened. Moments after the vote, Michaelis reports, she quietly walked into the room, wearing no ceremonial clothes or makeup. “Her fellow delegates then accorded her something that had never been given before and would never be given again in the United Nations: an ovation for a single delegate by all nations.”

Her private life had evolved in a radical new way — her last great unconsummated love, Dr. David Gurewitsch, had married a young art dealer and set up housekeeping in Manhattan. In 1959, after “three decades in which Eleanor had spent no more than 10 days in a row in any one apartment or home, or even in any one town and city,” Michaelis writes, she bought half a share of a townhouse in Manhattan where from age 75 on, she “lived under the same roof with the man she loved — and with that man’s wife.” She was a kind of precursor to the Gray Panthers, in a commune of her own choosing.

She died on Nov. 7, 1962, exactly 30 years after the day Franklin was first elected president. She had wanted a simple funeral, but, as Jackie Kennedy noted, it turned into an event “as complicated as an inauguration,” with the president, vice president, two ex-presidents, three first ladies (past, present and future) and the chief justice of the United States among the mourners.